- This topic has 4 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 4 years, 9 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

AuthorPosts

-

August 19, 2020 at 7:36 pm #749

Hans Hellinger

ModeratorHere is a Thread for historical magic.

A few tidbits:

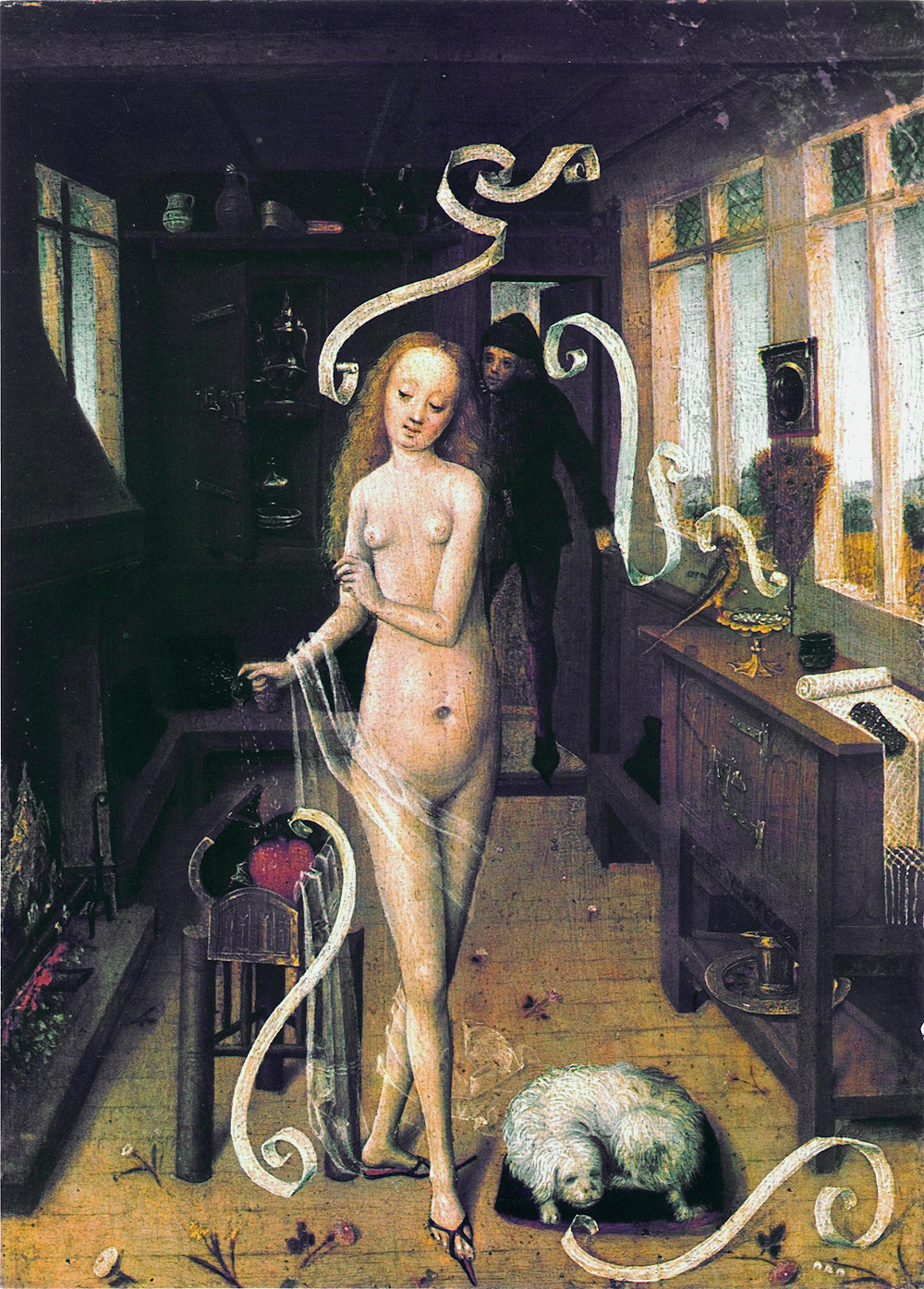

Anonymous 15th Century German painting of a woman casting a love potion

There are several important details in that image. The shoes, the peacock feathers, the bird (can you identify it?) the flowers on the ground, what she is holding in her right hand, the special mirror, what else is in her little coffer…

It is a bit obvious, but do you know who that is in this 19th Century painting?

And lastly, a short but important grimoire, the 15th century Liber Runarum, which you can read a good English translation of here

August 22, 2020 at 1:32 am #760Hans Hellinger

Moderator

A lot going on here in this painting. This gives a good introduction.

October 8, 2020 at 6:18 pm #1091Hans Hellinger

ModeratorWeapon magic and combat magic in Early Modern Germany. This article informed several of the spells in the Superno. I want to make a caveat without starting any kind of controversy hopefully, but I just think she overuses the term ‘hypermasculinity’ a bit. From my perspective, having been in a few fights in my life, anything which you might believe could preserve you from injury or death, whether rational (a more effective weapon or armor) or superstitious (some of the strange necromancy she describes in the article) might be welcome, irrespective of any gender perspective. The vast majority of people in armies and fighting duels were male, but not all of them (note the Czechs during the Hussite Wars as just one example). Down here where I’m from we also have Voodoo which some people will apply in various superstitious ways toward helping them in any kind of crisis, whether physical or otherwise. Anyway, with that caveat, it is a very interesting article. https://www.tandfonline.com/…/10…/13507486.2015.1028340

October 8, 2020 at 6:19 pm #1092Hans Hellinger

ModeratorAs an interesting additional commentary to this, I quote this passage from the Wikipedia article about Passau:

“During the Renaissance and early modern period, Passau was one of the most prolific centres of sword and bladed weapon manufacture in Germany (after Solingen). Passau smiths stamped their blades with the Passau wolf, usually a rather simplified rendering of the wolf on the city’s coat-of-arms. Superstitious warriors believed that the Passau wolf conferred invulnerability on the blade’s bearer, and thus Passau swords acquired a great premium. According to the Donau-Zeitung, aside from the wolf, some cabalistic signs and inscriptions were added.[5] As a result, the whole practice of placing magical charms on swords to protect the wearers came to be known for a time as “Passau art”. (See Eduard Wagner, Cut and Thrust Weapons, 1969.) Other cities’ smiths, including those of Solingen, recognized the marketing value of the Passau wolf and adopted it for themselves. By the 17th century, Solingen was producing more wolf-stamped blades than Passau was. ”

I found a Thread on Myarmoury about the so called Passau Wolf, with a neat photo of one on an antique blade http://myarmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.30320.html

The wolf from the Passau coat of arms:

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

October 8, 2020 at 6:51 pm #1094Hans Hellinger

ModeratorApparently the Passau Wolf goes back to a guild coat of arms granted by Emperor Charles IV in the 14th Century:

“In Germany, as far back as the thirteenth century, the cities of Passau and Solingen were famous for the production of sword blades, and early in the fourteenth century a celebrated armourer of Passau named Springenklee received from the Emperor Charles IV. a coat of arms bearing two crossed swords to be used by his township. The mark of the wolf, or running fox, as it is sometimes called, which is commonly associated with Solingen blades, was common to those of Passau as well, especially in the thirteenth century; it is supposed to have been granted to the Armourers’ Guild of Passau by the Archduke Albrecht in 1349. Until the custom was suppressed by the French, Solingen had a stamp office in its large market place, where the smiths were obliged to bring their work to have it proved and stamped.”

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 9 months ago by

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.