A siege in the pre-industrial eras was never fun for the participants. Sieges were often the most bloody, exhausting, and brutal engagements experienced by warriors and civilians of the pre-industrial world, and they haven’t gotten any more fun in modern times. But for a reader, safe in their own home or some comfortable library, the siege is a treasure trove of drama and fascinating events. Even for those who prefer genre fiction, you may find that some real sieges are often much wilder than anything in fantasy.

Three in particular which come to mind are the Siege of Rhodes in 304 BC, the Siege of Antioch in 1097 during the first Crusade, and the Siege of Malta in 1565

(all three places also had multiple other sieges, some of which are also quite interesting)

Siege of Rhodes 304 BC

During this period Rhodes was an independent and quite powerful little island city-state. Demetrius Poliocretes was a Ptolmaic / Macedonian tyrant descended from one of the generals of Alexander the Great, who controlled much of mainland Greece at this time. Demetrius decided he wanted to capture and occupy Rhodes as part of his general plans of expansion and conquest

What makes this siege stand out is that both sides were extremely advanced in siege warfare, to a level (arguably) not really matched until the late medieval period. Demetrius attacked with 170 ships and 40,000 men. During the peak of the siege he built a giant 130′ tall, six story siege tower called the Helepolis, which is now legendary. The sides of the tower were covered with iron and bronze plates. It was armed with 16 siege catapults and 4 ballistae. The largest siege catapult shot 82 kg stones. The tower weighed 160 tons and it took 3,400 men to move it with a special winch. Little shutters with mechanical doors opened and closed to protect the artillery crews. The tower had two large and fourteen small siege bridges.

This model of the Helepolis gives you an idea of the scale, though the real one at Rhodes was covered in bronze and iron plates.

The Rhodians were no slouches in siege warfare either though, and they created a device which is kind of like a propeller. We used to have a toy back in the day we called a ‘pond skipper’, which you would spin with your hands, like this thing:

So imagine one of those laid sideways, spinning fast, and rolling along the edge of the wall. The Rhodians deployed these and broke the siege bridges and anchor chains of the Helepolis which had approached their walls and was trying to breach. They used large ballistae shooting barbed javelins with chains attached to pull some of the protective metal plates off of the giant siege tower, exposing it to pyrotechnic substances. It was almost set ablaze so Demetrius had the tower pulled back out of range as his crews put the fires out. Eventually, after the siege had gone on for a year, Demetrius signed a truce with Rhodes and left with his army, abandoning his tower and much of his other siege equipment.

After the siege, the Rhodians dismantled the tower and created a massive statue to their sun god Helios next to the entrance to their harbor, which later became known as the Colossus of Rhodes

Siege of Antioch 1097-98

This was during the first Crusade in the 11th Century. There are several interesting characters on both sides but the most amusing is Bohemond I of Antioch, a rascal of a Norman knight of fairly low rank who rose to become one of the commanders of the Crusading forces largely through strength of character and fearsome fighting abilities. Born in 1054, twelve years before the Battle of Hastings, Bohemond grew up in the Norman principality of Taranto in what is now Southern Italy. His father was Norman, and he had Italian ancestry on his mother’s side. In effect, he was kind of like a Sicilian Viking. Let that sink in for a minute. We have a marvelous description of this guy from Byzantine princess Anna Comnena, who met him when she was fourteen. He made quite an impression on the young Greek aristocrat:

“Now the man was such as, to put it briefly, had never before been seen in the land of the Romans, be he either of the barbarians or of the Greeks (for he was a marvel for the eyes to behold, and his reputation was terrifying). Let me describe the barbarian’s appearance more particularly – he was so tall in stature that he overtopped the tallest by nearly one cubit, narrow in the waist and loins, with broad shoulders and a deep chest and powerful arms. And in the whole build of the body he was neither too slender nor overweighted with flesh, but perfectly proportioned and, one might say, built in conformity with the canon of Polycleitus… His skin all over his body was very white, and in his face the white was tempered with red. His hair was yellowish, but did not hang down to his waist like that of the other barbarians; for the man was not inordinately vain of his hair, but had it cut short to the ears. Whether his beard was reddish, or any other colour I cannot say, for the razor had passed over it very closely and left a surface smoother than chalk… His blue eyes indicated both a high spirit and dignity; and his nose and nostrils breathed in the air freely; his chest corresponded to his nostrils and by his nostrils…the breadth of his chest. For by his nostrils nature had given free passage for the high spirit which bubbled up from his heart. A certain charm hung about this man but was partly marred by a general air of the horrible… He was so made in mind and body that both courage and passion reared their crests within him and both inclined to war. His wit was manifold and crafty and able to find a way of escape in every emergency. In conversation he was well informed, and the answers he gave were quite irrefutable. This man who was of such a size and such a character was inferior to the Emperor alone in fortune and eloquence and in other gifts of nature”

The Seljuk Turks held Antioch, which was in the way of the Crusading army making their way down the coast of Syria toward their stated goal of Jerusalem. Antioch had been a Byzantine city and the Greeks asked the Crusaders to take it back for them. Many interesting and dramatic things happened in this siege but two stand out in particular.

First, the capture of the city. The Crusaders were besieging the town and Bohemond himself had defeated a Muslim relief force sent from Aleppo, but they were running out of food and there were rumors of other larger armies on the move. To get into the besieged town, Bohemond bribed one of the tower captains, a Christian named Firouz, who let ropes down from the tower windows. Bohemond and several of his men climbed into the castle and managed to cut their way to the gate and let their army in.

Second, the Battle of Antioch. Right after they captured the city, as the hungry and exhausted Crusaders began to celebrate their victory, a new and much larger Turkish army of 40,000 men arrived under the command of a notorious Seljuk warlord named Kerbogha. By this time of course the city itself was very low on food and supplies having just endured a siege and then absorbed thousands of Latin soldiers. The Crusaders, numbering about 20,000 men, had made enemies in town during the capture by slaughtering a bunch of civilians including many Christians who they couldn’t tell apart from the Muslims, meanwhile food and supplies were very scarce, so inside the town it was tense. A Byzantine army was on the way with supplies and more troops, but when the Byzantine Emperor heard about the arrival of Kerbogha’s army, he assumed the Crusaders were doomed, and pulled back his forces. The Crusaders fought off the first attempt to storm the walls, but the situation was dire. They were on the verge of eating their horses.

With the Crusading army were a number of fanatics. One wild-eyed and probably very smelly monk named Peter Bartholomew was digging in the floor of a chapel in the town, when he found a spearhead which he claimed was the spear of Longinus, the spear which had pierced Christ. Many relics purporting to be this “Holy Lance” already existed in Europe, and the commanders had their doubts as to this one’s legitimacy. However, noticing it created a stir among the starving and demoralized Crusader rank and file, Bohemond encouraged the crazed monk to spread the tale, and prepared a battle plan. On 28 June, the town gates opened, and fifteen thousand Crusaders charged out, swept up in religious fervor. Several eyewitnesses claimed to see visions of Saint George, Sinat Mercurious, and Saint Demetrius in the Clouds. The Crusaders were carried away with fighting spirit, and the Turks were unable to resist the charge, so Kerbogha attempted a feigned retreat, one of their standard tactics. But Bohemond was waiting for this, and when the Turkish flanking attack came, he hit it with his second cavalry force of 5,000 of his best equipped and motivated men, who came thundering out of the town gates in a second charge. The Turkish army was routed.

Bohemond of course, ended his Crusade right then and there, taking Antioch for himself, much to the chagrin of the Byzantines, who considered it their city, and his erstwhile French and Norman allies, who had expected him to accompany them on to Jerusalem. Antioch would be held by Bohemond’s descendants until 1268.

The Great Siege of Malta 1565

This was another Island siege, some consider it one of the greatest sieges of the pre-industrial period, and it is certainly epic. This time the attacker was the aggressively expanding Ottoman Empire which was gradually taking over the Mediterranean in the 16th Century. Rhodes had previously been the site of two epic sieges by the Ottomans, with the Latin defenders defeating the Ottomans in 1480 but finally falling in defeat in 1522. Malta is just south of Italy, between Sicily and North Africa, and at kind of the mid-point of the Mediterranean, a key strategic point. Latin polities, usually at odds, agreed that this site needed to be defended at all costs. But caught up in many other conflicts, and somewhat taken by surprise by the sudden Ottoman attack, they could not spare many troops.

The defense was lead by the Crusading Order the Knights Hospitaler of St. John / Malta. The Kingdom of Spain, the Pope, and the Italian city-states of Genoa and Florence also contributed forces, and there were also Maltese, Sicilian and Greek soldiers. The Ottomans were led by “Dragut” aka “The Drawn Sword of Islam”, a mighty pirate captain, as well as four other Ottoman Sea Pashas and two famous “Corsair” admirals from North Africa. They had elite Sipahi cavalry and at least 10,000 elite Janissary infantry, plus Ottomans, North Africans, and Arabs.

This battle was a huge mismatch. The Ottomans came with 45,000 men and hundreds of ships. The Christian forces amounted to 6,100, of whom only 2,500 were soldiers. The battle had several phases and was known for it’s extraordinarily innovative weapons and tactics, a few of which I’ll just list below.

- The Hospitaler, and notably the Florentine and Genoese Italian ships were outnumbered, but they were much faster and better made. Some of them had paid rowers who could fight instead of galley slaves that the Ottomans used. They were able to use hit and run attacks and disrupt Ottoman amphibious landings, supplies, and logistics, and were able to land friendly forces and supplies at some of their strong points on little islands. On a few key occasions they captured important Ottoman commanders in naval combats.

- The Hospitalers had a tiny force of about fifty old school knightly heavy cavalry based in a small but nearly impregnable castle several miles away from the main towns, lead by the Italian Hospitaler knight (born in Rhodes) Vincenzo Anastagi. At several points during the siege, this cavalry force sortied and attacked the Ottoman camp, catching them by surprise and doing major damage to logistics and morale, and they came right at the peak of the battle to attack the Ottoman at the key moment after they had finally breached the walls (more on this below).

- The close fighting involved other insanely diabolical siege devices. The Hopitalers deployed flame throwing tubes kind of like little bazookas called ‘trumps’, when the Janissaries approached the walls with siege ladders, they soaked giant “hula hoops” in linseed oil and gunpowder, lit them on fire and then threw them over the walls with tongs. These would surround small groups of Ottomans, trapping them and burning them alive. The Ottomans deployed sappers to dig tunnels, and the Maltese and Hospitalers, using barrels of water to detect underground vibrations, dug counter tunnels and moved up cannon, then suddenly breaking through the walls and blasting the sappers.

- The main Ottoman commander, Dragut, blew himself up after commanding a cannon crew to lower their barrel to shoot at a target on the wall of a Maltese fort, and the cannonball hit short and ricocheted.

- The Ottomans made a gigantic siege tower, higher than the walls of Birgu, which was protected by leather sheets, armed with multiple cannon and protected sharpshooters nests, and had a water tank to put out fires. To counter this, the Hospitalers had parts of the wall dug out and cannons moved up, with a thin layer of bricks still in front of them, when the tower came close, they knocked the bricks down and began blasting at point blank range with the hidden cannon using chain shot.

- The Hospitalers also stopped an amphibious assault by another battery of five hidden cannons, which waited until the enemy got close, then opened fire on an Ottoman amphibious landing force at a range of 200 yards, sinking almost the entire landing force in two salvos.

- At the key moment of the battle after the town walls of Birgu had finally been breached by a tunnel and a giant mine, with the defenders in a panic, the 70 year old Hospitaler commander, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette, who had been wounded several times and could no longer walk, put his armor on and had himself brought up in a chair right in front of the breach, and led the defense with about one hundred Hospitalers and other fighters who he had kept out of the fighting for three days to rest them. Just then the small cavalry force under Vincenzo Anastagi sortied from their castle and hit the huge Ottoman army in the rear, causing a panic and leading the Ottomans to withdraw.

- On Sept 7, after five months of the siege, a relief force of 8,000 Spanish soldiers was finally landed Malta, and charged the wavering Ottoman army, routing them.

After this, the Ottoman forces retreated. Estimates are they lost between 25,000 – 35,000 men. Stakes were very high, as most defenders were skinned alive or impaled when captured. Up to this point the Ottoman advance had been inexorable and they won more often than they lost. The Ottomans still had a formidable navy until the Battle of Lepanto six years later. After that the Latin kingdoms gradually became dominant in the Med.

A little more on medieval sieges in particular.

Towns, sortie tunnels and Cathedral towers

During sieges of medieval towns, which typically had very high towers either in churches or Cathedrals or their town hall, the townfolk would monitor the enemy forces, and pick the perfect time for attacks and followup attacks. Strasbourg did this during the Battle of Hausbergen against their own ‘fighting Bishop’ Walter von Geroldseck in 1262. First they attacked and captured a village church with a bell tower that the Bishops forces were using for their own lookout. Then the burghers sent a force out consisting of heavy infantry and crossbowmen, to attack the Bishop’s army coming to the relief of this village. First, there was a single combat between a knight from the burgher army, Marcus of Eckwersheim, and a knight from the bishop’s army called Beckelar. Both knights were unhorsed but von Eckwersheim was rescued by his allies while Beckelar was killed. Then the heavy infantry engaged the bishops cavalry while the crossbowmen prevented his infantry from joining the battle, while the commanders watched from the steeple of their tallest Church (their massive Cathedral having not yet been built). After about 20 minutes of tense, desperate fighting, at just the right moment, a second stronger infantry force came out of the town and routed the bishops men, capturing 86 of his knights and killing 70 knights and 1,300 infantry. The town only lost one soldier.

Walter von Geroldseck had his revenge though by being much more famous than the (usually forgotten) burgher victory of the tiny urban republic, having at least two action figures made of him, one of which is available on Amazon here for $175!.

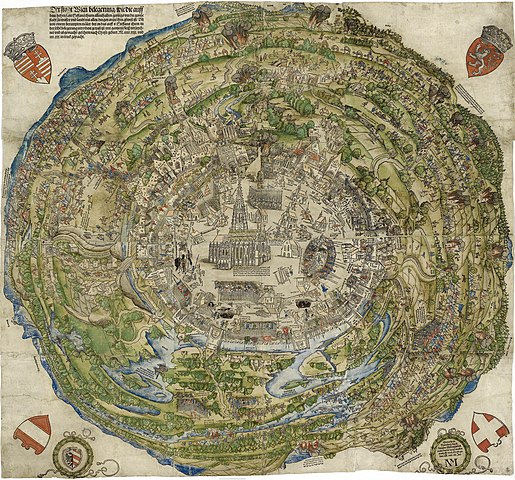

Similar tactics were used several times by towns all over Central Europe. In an attack on Krakow in 1287 during the Third Mongol invasion of Poland, a scout spotting the Mongol approach blew a trumpet to warn the defenders to close the gates. He was shot in the throat by a phenomenally skilled Mongol archer who hit him in the throat mid-blast, an event which is recreated every hour on the hour in Krakow. The Mongols were defeated in this raid which is a very big deal for Krakow, which had been sacked by the Mongols in 1241 and 1260, and had only just built received permission from a local Duke to build stone walls, which they had completed two years prior. Wroclaw / Breslau used their cathedral in a 15th Century siege by feared Heretic Knight-King George of Podeibrady of Bohemia, who rarely lost a battle. They watched his army as they dispersed to get supplies and the burghers sent sortie teams out of secret tunnels to attack isolated enemy troops and burn their supplies. Strasbourg did the same thing several times with observers on their massive 460′ Cathedral coordinating sorties when besieged in 1444 by the Dauphin of France and 25,000 Armagnac mercenaries. Perhaps the most famous use of this tactic was in Vienna during their sieges by the Ottomans. This painting by Nuremberg artist Nikolaus Meldemann depicting the siege of 1529 conveys a panoramic view of the Ottoman army around the city, as seen from their massive 136 meter / 448′ foot tall cathedral. Meldemann based his 1530 woodcut on a sketch created by an unknown artist who was present at the siege, and made his sketch from the Cathedral bell tower.

The Kings Mirror

A really good source for the diabolical ingenuity of High Medieval siege warfare is the “King’s Mirror” or Konugs Skuggsja of Norway. This outlines numerous fiendish siege inventions such as:

- Using molten glass (instead of boiling oil or pitch) to attack enemies close to the wall

- Making a device to spin a millstone (a large disk shaped stone about 1 meter wide) to a very high RPM, then unleashing it to fly bouncing down into the enemy ranks

- Sharpening the blade of a plowshare, welding it to an anvil, welding both to a heavy chain, then heating it red hot in a forge and swinging it down from the top of the wall just as the attackers place their ladders against it.

- Making a long chute with a wagon on a chain, with a heavy counterweight. Filling the wagon with white hot rocks, then dropping the counterweight to send the wagon down the chute to stop suddenly and hurl the superheated rocks down onto the enemy soldiers

- “Pond Skipper” type devices such as mentioned in the siege of Rhodes above

- And a mysterious device called a “stooping shield-giant which breaths forth flame and fire.” which the author praises as the most diabolical of all, but doesn’t explain in any detail.

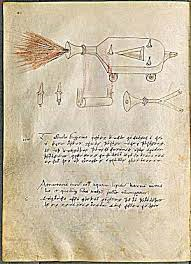

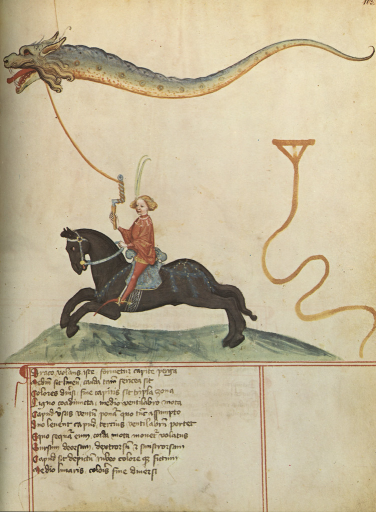

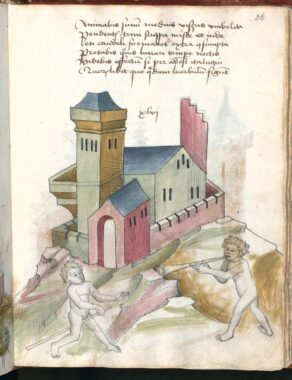

Siege Automata and other ‘Clockwork Punk’ technology.

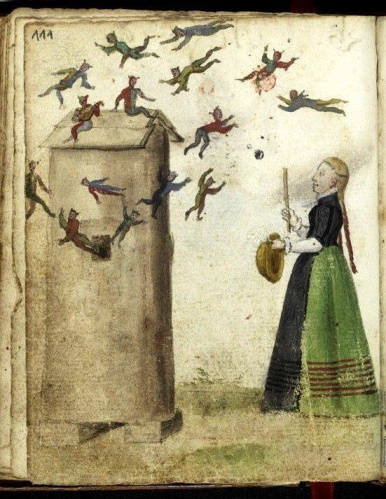

This mysterious “stooping shield giant” is the sort of thing mentioned in medieval documents which is routinely dismissed by modern scholars as fantasy, but it might actually have something to do however with siege automata. By the late 14th Century and fairly often in the 15th we see massive siege automata structures, sometimes created to look like dragons, devils or witches, with cannon and pyrotechnic devices. We don’t know much about their use but some of the plans are detailed enough to see that they could indeed have been made.

This for example is the “Feurhex”, a clockwork dragon or witch, which moves on rails and seems to emit flames from it’s mouth and head. it appears in a 1420 engineering book by 15th Century Venetian ‘wizard’ Giovanni Fontana.

This somewhat similar war-automata (probably from a German manual but I haven’t been able to track it down yet) is a dragon made of wicker with a cannon mounted in the mouth.

In the same book as the ‘feurhex’ Fontana also designed similarly fanciful looking mechanical rabbits and cats propelled by rockets

As weird as these look, they appear to be plausible designs though and have been tested in modern recreations. They also appear in several other military engineering manuals in the 15th-16th Centuries.

And a ‘magic lantern’ made to project the image of a Devil

By the later 15th Century there are dozens of war-engineering books, which the Germans called “Kriegsbücher”, appearing in both German and Italian-speaking areas. Some of the weird machines are clearly mechanical or plausible, but we don’t know what they are for. Like war-kites.

Which may have been for signalling or to terrify enemy horses. We also see medieval ‘scuba gear’ and many complex machines which are difficult to decipher but seem to be real, if somewhat baffling, ‘clockwork punk’ devices.

There are also things which were once thought fanciful but which we now know to be based in alchemical experiments or other real physics. Other elements of the Kriegsbücher however veer into strait up necromancy and black magic.

For genre fiction, computer games, or RPGs of course, these can be used as well!