Tagged: Crossbow

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 4 years, 12 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

AuthorPosts

-

July 23, 2020 at 11:02 pm #659

Hans Hellinger

ModeratorCrossbows in the Classical Period

The Greeks invented a variety of interesting crossbows, most seemingly for use in sieges, but some quite sophisticated designs were created. For example the late Classical ‘wizard’ Philo of Byzantium created repeating crossbows which were powered by a rotating chain, which could in turn be powered by a team of men or even oxen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philo_of_Byzantium

The Greeks also invented the Gastrophetes, a weapon with a clever mechanical system for spanning. These were basically a full sized bow with a mechanical spanner that could be locked. So it kind of had the advantages of both a bow and a crossbow.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastraphetes

The Romans mainly used torsion based weapons which were similar to but different than crossbows. These were used from ships, in sieges, and eventually also in open battle. They don’t tend to be discussed that much in terms of Roman warfare in modern times but they proved decisive in a variety of incidents, for example during Julius Caesars successful landing in Britain.

These have been re-created by a variety of Roman re-enactment groups, modern engineers and so on, but they have not yet achieved the performance reported by the Romans themselves. In general, for the Romans these were effective weapons but were heavy and bulky, and most were effectively ‘crew served’ weapons of limited tactical mobility.Crossbows in the middle ages

Crossbows of a new and different type began to proliferate in Latinized Europe some time in the Migration era and seem to have become more noticeable in the records during the Carolingian period, roughly around the 8th-10th Centuries. These were different from crossbows made anywhere else in the world in that they had a short ‘powerstroke’ – meaning that the arrow (quarrel or bolt) didn’t travel that far compared to a bow and usually wasn’t very long. They also tended to have shorter bows (prod or lathe) and some were quite compact. It’s important to point out that modern engineers and archers still don’t understand why the short power stroke method was chosen, as modern crossbows have long power strokes similar to bows.Along with some images I’m going to link some video clips by mainly two sources, Tod’s stuff or the workshop of Leo Toedeschini aka Tod, and Andreas Bichler.

Tod is an artisan who makes a wide variety of really cool medieval artifacts, from swords and knives to crossbows and much besides. He also does a series of videos demonstrating his creations. For crossbows he provides us with a very useful overview of all the basic forms and methods of spanning and so forth. Here is Tod’s website where you can buy all the stuff he makes and here is his video feed Tod’s Workshop where you can watch a variety of entertaining videos exploring medieval weaponry and other subjects.

Andreas Bichler is an Austrian academic and ‘living history’ practitioner who has done a very deep dive into the historical underpinnings of medieval weaponry and who has been making a series of crossbows with composite (non metal) prods since around 2005. In the last few years has managed for the first time that I know of to reproduce anything close to the kind of performance reported by medieval records, and shown by certain medieval antiques. Here is Andreas Bichler’s youtube channel, I couldn’t find any other site for him.

Here is a little summary on medieval crossbows from the Latin European context.

First, spanners. There were a variety of methods to span crossbows, some of which go back to early medieval or even classical times, others were late medieval inventions.

The stirrup

A stirrup on the business end of the crossbow was helpful in various methods of spanning and was often included in the design of a crossbow. The lightest weight weapons could be spanned using just hands and the foot stirrup (this is how most are spanned today)

Belt Hook

A hook attached to a belt was a common method for spanning lighter draw-weight crossbows. Had the advantage of being quick, and lets you use your legs and core muscles to span the the weapon instead of just your arms, which will give you more endurance.

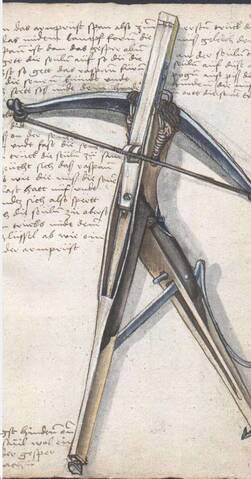

The windlass

Heavier crossbows couldn’t be spanned with muscle power alone, which is the reason the windlass was adapted to the weapon. This has the advantage of enabling a person of ordinary strength to span weapons of over 1,000 lbs draw (some even up to 1,500 lbs) but the disadvantage of being complex and a bit awkward to use.The ‘goats foot’ and the ‘wippe’

These are two similar inventions used to span lighter crossbows, for use from horseback (both in hunting and war). The most common type was called the “goats foot”. As you can see in the video, even a fairly inexperienced guy can get off quite a few shots with it. Somebody who grew up with these things hunting with them could probably do a bit better. The idea was to make a way to span them without using the foot (the normal method was using a foot stirrup) because on horseback you need your foot inside the saddle stirrups to control the horse.

Depictions of self-spanning ‘latchet’ crossbows from the Loeffelholz MS, 1505The Latchet Crossbow

The goats foot made it (arguably) possible to span a crossbow from horseback, but it was still not easy, and undoubtedly required a very highly skilled marksman and horseman, which translated to very expensive mercenaries. But medieval designers were very clever, and came up with another lighter weapon designed to use from horseback, with a [i]built-in spanner[/i] almost like a lever-action rifle. It’s something you have to see in action to believe so here is a video of Tod using a lovely replica he made of one.

The Cranequin

There still existed a need for more powerful crossbows that could be shot, and spanned, from horseback. This was probably the origin of the cranequin, a reduction gear device similar to the jack used to lift a car when changing a tire. These were expensive, sturdy tools, often of beautiful craftsmanship, and they continued to be made into the 18th Century as using crossbows for hunting from horseback remained popular for the nobility until the French Revolution.

Often they include astrological or magical symbols on them. This one was made in 1737Here is Andreas Bichler shooting a crossbow he spans with a cranequin, which gives you an idea how quickly it works.

An Arbalest with a cranqeuin and a variety of bolts, two for fowling (hunting birds) one for hunting big game (the barbed broad-head) and two military.

An exquisitely beautiful arbalest with an ivory grip, probably intended for hunting. From Fels Colonna, in the TyrolThe Arbalest

The type of crossbow used with the cranequin is usually referred to as an Arbalest, which is just a French word for crossbow. This represents a class of later medieval crossbow which was relatively small or compact, designed mainly for use from horseback but also used by infantry. They ranged from middling to high powered weapons, and were particularly useful for contending with horse archers in the Eastern frontiers of Latin Europe such as in Poland and Hungary. They could have steel or composite prods (made of wood, horn and animal ligaments) and were particularly popular in the Holy Roman Empire, the Low Countries, Switzerland and Bohemia. The Germans called these ‘stingers’ or ‘half tonners’, and they were known for killing a horse with a single shot out to a good distance.This is (so far as I know) the first modern replica of a medieval type crossbow which actually measures up to the performance reported for the Late medieval ones.

Andreas Bichler made it as part of his PhD dissertation and part of the design elements are secret, though I know one of the ingredients is the nuchal ligament of a horse (which keeps the horses head up without them having to think about it). Several previous attempts to do this (including some which also involved PhD dissertations) resulted in failures, weapons that either broke or lost power after two or three shots.

That is a 1,200 lb draw crossbow. The first half of the video shows a reconstruction of a special type of shield, a design originated by the Pagan Lithuanians for use against the Crusaders in the 14th & 15th Centuries – it too is kind of fascinating as the thing is notoriously bullet proof and the ingredients include some odd stuff like broken glass and iron filings mixed with gesso and applied over the wood in a kind of paste, under a sandwich of rawhide. The crossbow part starts at about the halfway point in the video.

Based on the velocity he got, and the weight of the bolt (81 grams at 69 meters per second), he got 192 joules. If we look at that in light of the testing done by Alan Williams in his Knight and the Blast Furnace, for an arrow penetration that is a bit over the equivalent of a .357 magnum. This type of weapon was supposed to have a range for shooting an individual target of about 80 meters and a total range (for a bunch of people shooting into an area) of about 320 meters. Modern tests with replicas get up to about 270 meters so far, but they are getting better with each generation.

Here you see a massive ‘wall crossbow’ flanked by two much smaller, but still potent arbalests (the one on the left being composite, and the one on the right is steel I think).The Wall crossbow

On the other end of the spectrum was the Wall Crossbow, a much bigger and more ungainly weapon primarily intended for sieges. These were also used in the field however from war-wagons. This is an even bigger one, a wall crossbow of 1270 lb draw, but a much larger crossbow shooting a much larger bolt (arrow). It’s the type of weapon mainly used either from inside a fort or from inside a war-wagon. Notice they are being very careful spanning it because if the prod snaps it could kill the guy. And he’s the first one to make one of these things work so he’s probably not certain of the reliability.On this one he got 433 joules. That is better than a .45 cal pistol, but you also have to remember that a .45 shoots a more or less round and soft lead bullet, whereas the crossbow is shooting a much heavier projectile with a sharp tempered steel arrowhead point. So the equivalent in penetration is closer to a modern hunting rifle. The point (pun intended) is to be able to reliably take down a horse with a single shot. A weapon of this category was supposed to have an effective range (for a human sized target) of about 200 meters, and a total range of close to 500 meters. The researcher Ralph Payne Galway shot an antique crossbow of this type approximately 450 yards in 1901.

Balestrino

an actual antique BalestrinoBalestrino crossbow

Finally from big back to small again – this little thing is called a ‘Balestrino’ it’s tiny little crossbow, almost toy sized. It shoots little darts. It’s unclear (and hotly debated) if it’s intended to be an actual weapon or more of a toy. My belief is that they were used in assassinations to shoot poisoned darts. It has a kind of built-in windup spanner

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 12 months ago by

Sam.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by

Sam.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by

Sam.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 11 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 10 months ago by

Hans Hellinger.

-

This topic was modified 4 years, 12 months ago by

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.